A Slain Lawman Finally Gets A Memorial Service, 100 Years Later

- Aug 10, 2021

- 13 min read

Updated: Aug 31, 2021

"DEPUTY DOUGLAS," as he has come to be known by law-enforcement brothers and sisters who never met him, is finally getting a formal memorial service from the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office.

It’s only taken 100 years.

A reluctant rookie whose legacy as PBSO’s first deputy killed in the line of duty was nearly lost in history, George Clem Douglas was shot to death on Aug. 27, 1921, as he tried to arrest a robbery suspect.

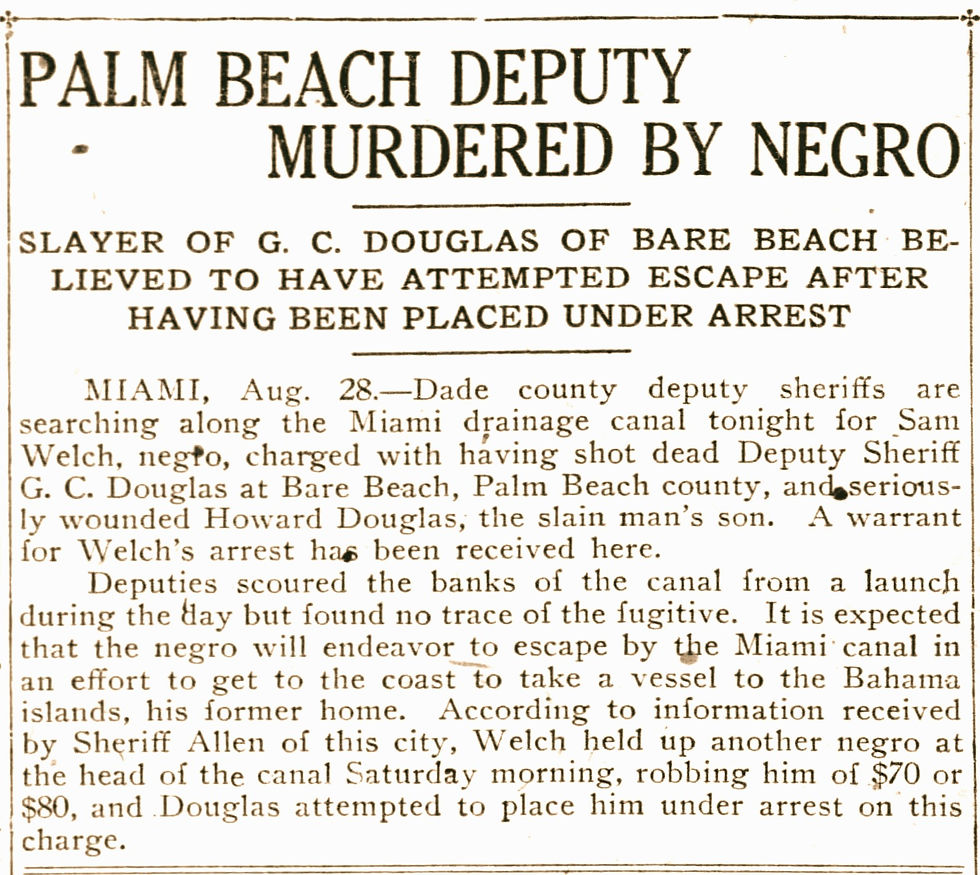

His murder, on the south shore of Lake Okeechobee between South Bay amd Clewiston, made viral headlines from Miami to the Carolinas.

But as the years and decades rolled by, hurricanes and storms washed away the settlement and graveyard where he lived, patrolled and was buried. His story all but faded from public memory, kept alive by the faint recollections of Douglas descendants.

It might have disappeared forever if not for the tenacious determination of three deputies from two different generations, lawmen driven by a shared commitment to uphold the inscription on the polished marble Fallen Deputies memorial at PBSO headquarters:

“To serve and protect was their oath. To honor them is our duty.’’

For retired Lt. David Estes, Capt. John “JB” Killingsworth and Lt. John Chapman, there’s no expiration date, no statute of limitations, on fulfilling the inscription’s second sentence.

It was Estes who made sure PBSO recognized Douglas’ death when the agency learned about it in 1995, from a professor who’d stumbled on it while researching a book about slain police officers.

It was Killingsworth and Chapman who picked up earlier this year where Estes left off when he retired in 1998, trying to find and mark the crime scene and burial plot.

In May, they launched Operation Locate, a task force of federal, state and local partners — archeologists, engineers and surveyors, law enforcement officers, museum curators and amateur historians.

They’re certain they’ve found the general area where Douglas died that Saturday afternoon 100 years ago. They believe they are closing in on his grave site, 4 miles west of the crime scene.

Along the way, they learned bits of history, drama and plot twists in a tragic story about a reluctant hero and the ripple effects his murder would have on future generations.

Later this month, they’re planning to give Douglas what he never received in 1921: a proper law-enforcement memorial service, the same solemn 21-gun salute and playing-of-Taps ceremony given to any deputy killed in the line of duty.

It will take place on the 100th anniversary of his death, on the same patch of earth next to the old Miami Canal locks where he took his last breath.

“We want to give Deputy Douglas the proper memorial and ceremony he should’ve gotten back in 1921, to make sure his memory stays alive,’’ Chapman said on a steamy July morning as he stood with his two co-investigators on a gravel road south of Lake Okeechobee.

“It will be with full honors,’’ Killingsworth said.

"We owe it to the guy," Estes said.

HE WASN’T YOUR typical rookie cop.

A farmer and remarried widower, George Clem Douglas was 50 years old when he was deputized on July 19, 1921, just 12 years after state lawmakers carved Palm Beach County out of Dade County.

A year earlier, he’d moved his family from Alabama to a settlement on the south shore of the big lake, just east of Clewiston, called Bare Beach.

Known for his athleticism and fearlessness, he quickly won the respect of his new neighbors.

He enjoyed swimming and baseball.

He was a productive farmer. He served on a community advisory board.

He was active in civic events like the "autocade" that celebrated the opening of a highway from West Palm Beach to Belle Glade on June 24, 1921.

Clem, as his family called him, had no burning desire to work in law enforcement. But when the Ritta-Bare Beach Community Council requested his services that summer with a unanimous vote, he reluctantly accepted.

He was just five weeks on the job when duty called for the last time.

On Aug. 27, 1921, he was coaching the Bare Beach team at a baseball game in Moore Haven when someone showed up yelling something about a “negro” laborer at the canal locks robbing another man of his paycheck, according to accounts.

A boat ride back across the lake would take too long. So, the rookie deputy got behind the wheel of a borrowed Model-T pickup.

With a loaned World War I pistol at his side and his 19-year-old son in the passenger’s seat, he sped off to make an arrest.

LAKE OKEECHOBEE CATFISHING was one of Palm Beach County’s most lucrative industries in the 1920s, with 6 million pounds of the fish being pulled in one year, County Archeologist Chris Davenport says in a 2012 video about the history of the big lake.

Getting the fresh catches to dinner tables and restaurants around the world required a seamless transportation partnership with steamships and railroads.

In 1921, the Southern Steamship Company was constructing locks at the head of the Miami Canal to help ships move in and out of the lake more efficiently. That meant quicker transport of fresh Lake Okeechobee catfish to Henry Flagler’s refrigerated train cars.

Building the locks required hundreds of workers, many of them African American like 50-year-old Sam Wells.

A native of Georgia with a bushy mustache and hair streaked with gray, Wells was a veteran laborer on canal locks and public works projects from Melbourne to Homestead, one newspaper reported.

He lived among the workers in a labor camp just steps from the Miami Canal locks construction site. On weekends, they sometimes blew off steam by fishing, playing cards and gambling.

On that Saturday afternoon in 1921, a row erupted in the camp.

Wells had been accused of cheating another laborer out of his $89 paycheck — about $1,200 in today’s money — in a gambling game called skins, according to newspaper stories.

A complaint was promptly filed. The new deputy was sent for.

AROUND 5:30 P.M. Douglas and his son Howard arrived at the labor camp.

As they approached a workhouse shack, Wells called out to ask what Douglas wanted, according to a letter written two days later by Douglas’ 15-year-old daughter to her sister in Alabama.

“‘Papa said, ‘Never mind what I want. You come here,’’’ Addie Mae Douglas wrote.

A sharp crack rang out. Deputy Douglas fell.

“They were standing by the window and he shot papa with a high power rifle,’’ Addie Mae said in the letter.

The son stooped over his dying father, trying to protect him from further harm, when another shot rang out. Howard was hit in the back, the bullet piercing his lung.

In the chaos, Howard was lucid enough to stuff the corner of his shirt into the bullet hole, stemming the bleeding and probably saving his life, before he was taken by speed boat a day later to Good Samaritan Hospital in West Palm Beach.

Wells fled the scene and disappeared into the swamps.

WELLS WAS NEVER caught, despite cash rewards and exhaustive searches, including one that led to the friendly-fire death of a Miami police officer mistakenly shot Nov. 28, 1921, by a Dade County deputy who thought he was closing in on Wells.

Wells’ wife and niece were taken into custody, perhaps to flush out Wells or to protect them from mobs angry that a Black laborer had killed a white deputy.

When they were transported from Bare Beach to the jail in West Palm Beach, among the passengers they shared the boat ride with was Douglas’ widow.

Della Douglas was on her way to Good Sam to see her wounded son, who was not expected to survive in the first few days. But Howard Douglas battled back and recovered.

He would get married a year later, have four kids and work at the U.S. Post Office in West Palm Beach for 34 years before passing away in 1969 at the age of 67.

But as he teetered on the brink of death at Good Sam, his father’s murder was reverberating across South Florida and the southern United States.

Viral headlines and stories in September and October exploited the suspect’s race by using a word commonly accepted the time — “Negro.”

The 1921 Labor Day celebration was canceled, the money for the event given to Della Douglas. Deputy Douglas’ body was taken to Bare Beach and interred.

“Papa was buried yesterday. Sure was sad,’’ Addie May wrote to her sister on Aug. 29, 1921. “I don’t know what will become of us. We are left daddiless. Oh my....’’

LESS THAN THREE years later, around the time Douglas’ family left Bare Beach and moved to West Palm Beach, another Palm Beach County sheriff’s deputy was killed in the line of duty.

On Jan. 9, 1924, Deputy Frederick Baker was gunned down near modern day Hobe Sound during a shoot-out with the Ashley Gang, a notorious band of outlaws with a talent for robbery, moonshine and murder, including the killings of two police officers in Dade County.

In 1994, the Palm Beach County Sheriff’s Office dedicated its Fallen Deputies Memorial, a polished marble wall engraved with the names of the nine deputies killed (up until that time) in the line of duty.

At the ceremony, Baker was publicly recognized as the agency’s first deputy to die in service.

A 1994 newspaper story about the wall dedication reported that Baker had been unintentionally forgotten, perhaps because of records destroyed in the 1928 hurricane, until his slaying was uncovered “through recent research” by the sheriff’s office.

Although PBSO didn’t know it at the time, Baker was not the agency’s first deputy killed in the line of duty.

It would be another year before that fact came to light, and it would happen by chance.

ONE DAY IN 1995, Lt. David Estes was sitting in his District 5 office in Belle Glade when he received a phone call from a professor at Florida International University.

The professor, William Wilbanks, was researching a book about slain law enforcement officers from Florida, Texas and South Carolina. While scouring old news clippings, Wilbanks said, he’d come across a Greenville, S.C., newspaper article about the 1921 death of another officer, someone named George Clem Douglas from the Palm Beach County Sheriff's Office.

Estes was stunned.

“I sat at my desk and thought about it: I may have stood on that man's grave and didn't know it,’’ said Estes, who joined PBSO in 1971 and patrolled the Glades.

Skeptical about the accuracy of an old article from a newspaper in South Carolina, he did some research of his own. At the Belle Glade library, he came across an account of the Douglas’ murder in Ruth Robbins Beardsley’s 1973 book, “Pioneering in the Everglades.”

He also spoke to Douglas’ daughter, Ruth. “She was an elderly lady, petite, and pretty feisty,’’ he recalled with a laugh. “She gave me enough general information that I believed it had happened.’’

After Estes’ lobbying, PBSO added Douglas’ name to the Fallen Deputies Memorial in 1996. (It is spelled as “Douglass,’’ the result of an error that would be discovered 25 years later.)

Estes was proud of his role, thanks to the tip from Wilbanks, to honor Douglas with public recognition.

But he knew his mission wasn’t complete.

He wanted to find the precise locations where Douglas was killed and buried. It would be an exercise in frustration.

“I talked to a lot of old timers who were here in the ‘30s, farmers, packing house people, retail people, and nobody had ever heard of this. They had no knowledge of this,” Estes said.

He paused to compose himself.

“That's what spirited me on,'' he said. "To think that nobody knew, that was devastating.’’

In 1998, Estes retired, frustrated over his inability to find the crime scene and burial spot of Deputy Douglas.

“I think about him every day,” he said in July.

"He was just lost in the disasters, I guess.”

FOR 25 YEARS, the case went cold.

Then, one day in March, a Marine with an eye for detail picked up the torch.

Capt. John “JB” Killingsworth, who joined PBSO the year Estes retired, has had a productive career. He served as SWAT commander in 2013 and oversaw the agency’s special operations in 2017 when Chinese President Xi Jinping visited then-President Trump in Palm Beach.

He’s currently in charge of PBSO’s training division. While revamping the agency’s New Hire Academy this spring, he wanted to include a section about the 15 deputies killed in the line of duty.

Reading up on the Douglas case, Killingsworth said he realized a glaring omission: The slain rookie deputy “never received a proper law enforcement memorial or funeral.”

He realized something else: The 100th anniversary of Douglas’ murder was fast approaching and the agency still didn’t know where the crime occurred or where he was buried.

All of that was unacceptable, Killingsworth said.

He turned to Lt. John Chapman, 34, a homicide detective who joined PBSO in 2006 and is regarded as one of the agency’s finest investigators.

One investigation took Chapman to Cuba, where he worked with the State Department and Department of Justice in 2015 to arrest and convict a Cuban national for murdering a Jupiter doctor. It was the first time that a U.S. law-enforcement officer testified in Cuba for a criminal case, PBSO said.

In the search for Douglas’ grave and crime scene, essentially the equivalent of a 100-year-old cold case, Killingsworth knew Chapman’s skills would come in handy.

For one, they don’t think any maps of 1921 Bare Beach exist, assuming they were ever drawn in the first place.

Also, much of the area Douglas patrolled — including settlements of Bare Beach and Ritta — was washed away over the years by hurricanes and storms.

Another wrinkle: The boundaries of Lake Okeechobee were redrawn after the construction of a dike following the 1928 hurricane.

It seemed like a hopeless cause.

The two veteran investigators were undaunted.

THEY LAUNCHED “OPERATION LOCATE,’’ a name as simple as the task force’s mission.

They enlisted a diverse roster of partners, from the state Historical Resources and Clewiston Museum to the South Florida Water Management District and U.S. Postal Service.

“You can't imagine the cadre of people they've collected as volunteers,’’ said task force member George C. “Chappy” Young, founder of the mapping and surveying company GCY Inc.

“I bet you there's 50 to 100 people working on this, from Washington D.C. to Palm Beach County.’’

They scoured what maps they could find.

They dug up old news clippings and studied yellowing maps, some drawn by hand in the 1920s.

They used computers to overlay those old maps with modern Google Earth maps.

Confident that the crime scene was next to the canal locks, they started knocking on the doors of nearby homes, many of them built where the labor camp once stood.

Standing at 74-year-old Barbara’s Austin’s front door one day in June, Killingsworth introduced himself and started explaining why he was there.

Austin interrupted him.

“She goes, ‘Oh, you mean Deputy Douglas who was killed right there,’ and she pointed to the side of the lock” less than 100 yards from her home, which in 1921 served as the cantina to feed the laborers building the locks, Killingsworth said.

“That just cemented all our research that we were in the right location.’’

THE BURIAL SPOT has been more of a challenge to find.

Searching for it unearthed a few surprises.

While researching the graves of Douglas’ descendants, Killingsworth made an unsettling discovery: Douglas’ name has been spelled two different ways in newspaper clippings since the 1920s — ending either with one “s” or two.

His heart sank when it dawned on him that PBSO’s Fallen Deputies memorial wall was engraved with the incorrect spelling.

“That set me on fire,’’ Killingsworth said, “I come from 15 years in the Marine corps. It's our job to honor. If we have to correct a misspelling, I'm going to make that happen.’’

In their efforts to find Douglas’ century-old gravesite, they’ve turned to the latest modern technology.

Using old maps blown up on an iPad screen, they looked for the locations of since-gone landmarks — post office, a church, a school house — near the land once used as the Bare Beach graveyard.

They shared their evidence with Estes, 72, who joined the two deputies at least once this summer on a walking search for the gravesite.

They haven’t found it yet, but they think they are within a 200-yard radius of it.

“Everybody has kind of caught this bug that we are going to find him, one way or another,’’ Killingsworth said.

“It may take several years. All we have to do is keep looking.’’

GROWING UP IN Virginia, Kaye Henyon heard vague family stories about an ancestor getting killed while working as a law-enforcement officer in Florida a long time ago.

Most recently, her father talked about it before he passed away in 2016.

“I didn’t know much about the story other than his great-grandfather was shot in the line of duty,’’ she said.

One day in June, she received a call from Killingsworth. He shared everything the task force had learned and he invited Henyon and her family to the Aug. 27 ceremony.

After Henyon hung up, one particular detail shared by Killingsworth resonated with her — how her great-great-grandfather, Howard Douglas, had the wherewithal at the age of 19 to stuff his bullet wound with the corner of his shirt.

“It was a miraculous event, how his son was able to save his own life, which created my family line,’’ she said.

“The one thing that went through his head” as he lay bleeding from the gunshot “was what led to the creation of my family.’’

Because Howard Douglas survived that awful afternoon in 1921, he was able to get married and start a family. A daughter, Marion Rhoads, gave birth in 1944 to Richard “Doug” Rhoads.

A native of Miami, Rhoads attended the University of Florida and served in Vietnam. He was the father of three children, including Henyon, and enjoyed a colorful career in law enforcement and college football.

He worked as an FBI agent and a police officer in Virginia. He also officiated Atlantic Coast Conference games, later serving as an analyst for ESPN and NBC Sports, providing on-air rules explanations during games.

After learning in 1995 about his great-grandfather’s death, he helped petition the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial in Washington D.C. to include Douglas’ name.

He sent a copy of the letter Douglas’ daughter wrote to her sister in 1921 two days after their father’s murder.

In his petition, Rhoads said he “was moved by her reference that ‘we haven’t got any more Daddy’ and that ‘I don't know what will become of us. We are left daddiless.’

“The letter was maintained in my family for over 75 years,’’ he wrote, “It is a poignant and sorrowful reference to what so many other children have suffered in the years that followed.’’

Before he died at age 71 in 2016, just weeks after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, Doug Rhoads enjoyed fishing and boating with his grandchildren.

He often shared stories about his law-enforcement career and about Deputy Douglas, whose photo was displayed in his office at home.

“They are totally fascinated by it,’’ Henyon said about her children’s reaction to the Douglas story.

For Henyon’s family, PBSO’s memorial service for Douglas will provide another measure of closure.

ON THE MORNING of Aug. 27, some of Douglas' descendants will gather with Sheriff Ric Bradshaw, dozens of deputies and a riderless horse near the head of the Miami Canal south of Lake Okeechobee.

In the shade of a strangler fig, a shiny granite monument will be dedicated and placed at the fence line next to the old locks.

A bugler will play Taps. Marksmen will fire a 21-gun salute. A squadron of helicopters will buzz overhead. A flag will be folded and presented to a Douglas relative.

And after prayers and remarks, the radios of deputies across Palm Beach County will crackle with a dispatcher’s voice paying a final, long overdue tribute to Douglas:

“10-07, deputy out of service.”

When the ceremony ends, Operation Locate will resume.

“I once said that it’s the rite of passage for Douglas, for us to know who he was and why he was killed and where he was killed and where he was buried,’’ Estes said in July.

As he spoke, he stood with his co-investigators on the side of a lonely road not far from where they think Douglas was buried in 1921.

He sounded like an old detective still haunted by that one case he could never solve.

“I didn’t have the resources,’’ he said, after pausing for several seconds to gather his emotions.

“That’s why we’re here,’’ Killingsworth said. “We want to solve it for you.’’

A faint smile creased Estes’ face.

“Find it quick,’’ he said with a chuckle.

“We’re on it,’’ Killingsworth replied.

© 2021 ByJoeCapozzi.com All rights reserved.

Sign up for a free subscription to ByJoeCapozzi.com

IN CASE YOU MISSED my previous blog: You Don't Have To Be James Bonds To Sneak Aboard and Jump Off a Russian Freighter.

MUSIC FROM OTHER KEYBOARDS

John Fetterman in the Louisville Times and Courier-Journal: Pfc. Gibson Comes Home

Victoria Kim in the Los Angeles Times: Next stop, a town at risk of disappearing. Please, watch your bones

Jon Lee Anderson in The New Yorker: The Murder Scandalizing Brazil’s Evangelical Church